Head and neck anatomy is a comprehensive study of the structural organization of the region‚ including bones‚ muscles‚ nerves‚ and glands. It is essential for understanding human morphology and its clinical implications‚ providing foundational knowledge for medical professionals and students. The anatomy of the head and neck is detailed in various textbooks and resources‚ such as Textbook of Head and Neck Anatomy and Clinical Head and Neck Anatomy for Surgeons‚ which offer in-depth insights into surgical landmarks‚ regional dissection‚ and pathological conditions. This field is vital for diagnosing and treating conditions like torticollis‚ thyroid disorders‚ and cranial nerve abnormalities‚ making it a cornerstone of medical education and practice.

1.1. Definition and Scope of Anatomy

Anatomy is the scientific study of the structure of organisms‚ focusing on the internal and external organization of living beings. Derived from the Greek word anatomē (dissection)‚ it examines the physical arrangement of tissues‚ organs‚ and systems. The scope of anatomy encompasses both macroscopic and microscopic structures‚ providing a foundational understanding of how organisms function. In the context of the head and neck‚ anatomy includes the study of bones‚ muscles‚ nerves‚ glands‚ and blood vessels‚ essential for medical professionals. Textbooks like Textbook of Head and Neck Anatomy and resources such as Clinical Head and Neck Anatomy for Surgeons detail these structures‚ emphasizing their clinical relevance and surgical significance.

1.2. Importance of Studying Head and Neck Anatomy

The study of head and neck anatomy is crucial for understanding the complex interrelationships of structures in this region. It is essential for medical professionals‚ particularly surgeons‚ dentists‚ and radiologists‚ due to the high concentration of nerves‚ blood vessels‚ and glands. Mastery of this anatomy aids in diagnosing and treating conditions like tumors‚ infections‚ and trauma. It also underpins surgical planning‚ ensuring precise dissection and minimizing complications. For educators and students‚ it provides a foundational framework for learning and teaching. Resources like Anatomy of the Head and Neck emphasize its clinical relevance‚ making it indispensable for both academic and practical applications in healthcare.

Bones of the Skull and Face

The bones of the skull and face form a complex framework‚ providing protection for the brain and supporting facial structures; They enable movement and function.

2.1. Cranial Bones

The cranial bones form the skull’s framework‚ protecting the brain. They include the frontal‚ occipital‚ parietal‚ temporal‚ sphenoid‚ and ethmoid bones. These bones fuse during adulthood‚ creating a rigid structure. The frontal bone forms the forehead and part of the eye sockets‚ while the occipital bone surrounds the foramen magnum at the skull base. Parietal bones make up the roof and sides‚ and temporal bones house the inner ear structures. The sphenoid and ethmoid bones are complex‚ contributing to the cranial base and nasal cavity. Together‚ they provide structural support and protection‚ with sutures allowing limited movement. Their fusion ensures cranial stability while accommodating muscle attachments and sensory functions.

2.2. Facial Bones

The facial bones‚ totaling 14‚ form the skeletal structure of the face‚ contributing to its shape and functionality. They include the maxilla‚ zygoma‚ nasal bones‚ lacrimal bones‚ palatine bones‚ inferior nasal conchae‚ and mandible. These bones support facial muscles‚ forming features like the jaw‚ cheeks‚ and orbits. They also house sensory organs and create cavities for the eyes‚ nose‚ and mouth. The maxilla and zygoma form the upper jaw and cheekbones‚ while the nasal bones shape the nose. These bones fuse during growth‚ providing stability and enabling functions like chewing and facial expressions. Their intricate arrangement balances aesthetics with functional needs‚ making them vital for both structure and expression in the head and neck region.

2.3. Mandible and Maxilla

The mandible‚ or lower jawbone‚ is the strongest facial bone‚ forming the lower jaw and anchoring teeth. It articulates with the temporal bone at the temporomandibular joint‚ enabling chewing and speech. The maxilla forms the upper jaw‚ holding the upper teeth and contributing to the orbit and nasal cavity. Both bones are vital for facial structure and function. The mandible’s alveolar process supports the lower teeth‚ while the maxilla’s alveolar process supports the upper teeth. The maxilla also contains the maxillary sinus‚ the largest paranasal sinus. Together‚ these bones facilitate essential functions like mastication‚ speech‚ and breathing‚ while providing structural support to the face and head.

Muscles of the Head and Neck

The muscles of the head and neck enable facial expressions‚ chewing‚ and neck movements. They include skeletal muscles like the masseter and sternocleidomastoid‚ vital for function and expression.

3.1. Facial Muscles

The facial muscles are a group of skeletal muscles responsible for controlling facial expressions. They are innervated by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). Key muscles include the orbicularis oculi‚ zygomaticus major‚ and buccinator. The orbicularis oculi surrounds the eye‚ enabling blinking and eyelid closure. The zygomaticus muscles facilitate smiling by elevating the mouth corners. The buccinator aids in forming facial expressions and assists in chewing. These muscles originate from bones like the zygomatic‚ maxilla‚ and mandible‚ and they insert into the skin or other muscles. Their functions extend beyond expressions‚ contributing to actions like chewing and speaking. Understanding their anatomy is crucial for both medical procedures and appreciating their role in social communication and emotional expression.

3.2. Muscles of Mastication

The muscles of mastication are responsible for controlling jaw movements‚ enabling functions like chewing‚ speaking‚ and maintaining facial expressions. The primary muscles include the temporalis‚ masseter‚ medial pterygoid‚ and lateral pterygoid. The temporalis muscle originates from the temporal bone and inserts into the mandible‚ facilitating jaw elevation and retraction. The masseter muscle‚ originating from the zygomatic arch‚ assists in jaw closure. The medial and lateral pterygoid muscles work together to open the mouth‚ protrude the jaw‚ and facilitate lateral movements. These muscles are innervated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. Their coordinated action is essential for effective mastication and maintaining proper occlusion of the teeth.

3.3. Neck Muscles

The neck muscles are divided into two main groups: the anterior and posterior triangles. The anterior triangle includes the sternocleidomastoid‚ the largest neck muscle‚ which originates from the sternum and clavicle‚ inserting into the mastoid process. It facilitates head rotation and neck flexion; The infrahyoid muscles‚ such as the sternothyreoideus‚ omohyoideus‚ sternohyoideus‚ and thyrohyoideus‚ depress the hyoid bone and larynx‚ aiding in swallowing and speech. The posterior triangle contains muscles like the trapezius‚ which assists in shoulder movements. These muscles are innervated by the cervical plexus and accessory nerve‚ playing crucial roles in head and neck mobility‚ respiratory support‚ and maintaining posture.

Nervous System of the Head and Neck

The nervous system of the head and neck includes cranial nerves‚ cervical plexus‚ and sympathetic chains. Cranial nerves originate from the brainstem‚ controlling sensory‚ motor‚ and parasympathetic functions. The cervical plexus‚ formed by cervical nerves‚ supplies neck muscles and skin‚ aiding in movement and sensation.

4.1. Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerves are essential components of the head and neck nervous system‚ originating from the brainstem. There are 12 pairs‚ each with specific functions. The trigeminal nerve (CN V) manages facial sensation and chewing‚ while the facial nerve (CN VII) controls facial muscles and taste. The vagus nerve (CN X) regulates heart rate‚ digestion‚ and speech. Cranial nerves also include the olfactory (CN I) and optic (CN II) nerves‚ responsible for smell and vision‚ respectively. These nerves are crucial for sensory and motor functions‚ including swallowing‚ hearing‚ and eye movements. Damage to cranial nerves can lead to significant deficits‚ highlighting their importance in head and neck anatomy.

4.2. Cervical Plexus

The cervical plexus is a complex network of nerves located in the neck‚ arising from the ventral rami of cervical vertebrae C1 to C4. It plays a crucial role in innervating the muscles and skin of the neck‚ as well as contributing to the phrenic nerve‚ which controls the diaphragm. The plexus forms the cervical ansa‚ a loop of nerves supplying the infrahyoid muscles. Its branches include the sensory transverse cervical nerve and the motor branches to the neck muscles. Damage to the cervical plexus can result in impaired neck movements or sensory loss. Understanding its structure is vital for head and neck surgeries and diagnosing neurological conditions.

Blood Vessels and Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system of the head and neck includes cervical lymph nodes‚ which drain and filter lymph from the region‚ playing a key role in immunity and diagnostics.

5.1. Arteries of the Head and Neck

The arterial supply to the head and neck primarily originates from the common carotid and subclavian arteries. The common carotid artery bifurcates into the external carotid artery‚ supplying the face‚ scalp‚ and neck‚ and the internal carotid artery‚ which primarily serves the brain and eyes. The subclavian artery gives rise to the vertebral artery‚ contributing to the posterior circulation of the brain. Key branches include the facial‚ maxillary‚ and superficial temporal arteries from the external carotid‚ and the ophthalmic artery from the internal carotid. These arteries form anastomoses‚ ensuring collateral circulation‚ critical for maintaining blood flow in case of occlusion. Their intricate network supports vital functions in the head and neck region.

5.2. Veins of the Head and Neck

The venous drainage of the head and neck is primarily managed by the jugular‚ facial‚ and retromandibular veins. The internal jugular vein‚ the largest‚ drains blood from the brain‚ face‚ and neck into the brachiocephalic veins. The external jugular vein collects blood from the scalp and superficial structures‚ emptying into the subclavian veins. The facial vein‚ rich in anastomoses‚ drains the face and connects to the cavernous sinus. Deep cerebral veins and the cavernous sinus are critical for intracranial drainage. The dural venous sinuses collect blood from the brain and drain into the jugular veins. This venous network ensures efficient blood return and maintains cranial pressure‚ with clinical relevance in conditions like thrombosis or facial vein infections. Its complexity highlights the need for precise anatomical understanding in medical procedures.

Glands of the Head and Neck

The head and neck contain vital glands‚ including salivary glands essential for digestion and the thyroid gland regulating metabolism. Their proper function is crucial for overall health.

6.1. Salivary Glands

The salivary glands are essential for producing saliva‚ which facilitates digestion‚ lubrication‚ and maintenance of oral health. There are major and minor salivary glands. The major glands include the parotid‚ submandibular‚ and sublingual glands‚ each with distinct locations and functions. The parotid glands are the largest and are located anterior to the ears‚ secreting serous saliva. Submandibular glands‚ situated beneath the mandible‚ produce both serous and mucinous saliva. Sublingual glands‚ under the tongue‚ primarily secrete mucinous saliva. Minor salivary glands are distributed throughout the oral mucosa. Dysfunction or inflammation of these glands can lead to conditions like xerostomia or sialadenitis‚ impacting oral and systemic health.

6.2. Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland is a vital endocrine organ located in the neck‚ anterior to the trachea and below the larynx. It consists of two lobes connected by an isthmus‚ with the entire gland enveloped by pretracheal fascia. The thyroid plays a crucial role in regulating metabolism‚ growth‚ and development by producing hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). These hormones are essential for cellular energy production and metabolic balance. The gland is supplied by the superior and inferior thyroid arteries‚ with venous drainage via thyroid veins; Lymphatic drainage occurs through the deep cervical lymph nodes. Disorders of the thyroid‚ such as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism‚ can significantly impact overall health and bodily functions.

Surgical Anatomy of the Head and Neck

Surgical anatomy focuses on key structures‚ such as blood vessels‚ nerves‚ glands‚ and fascial layers‚ crucial for safe and effective surgical interventions in the head and neck region.

7.1. Surgical Landmarks

Surgical landmarks in the head and neck are critical for identifying key anatomical structures during procedures. These include bony prominences like the mastoid process‚ styloid process‚ and thyroid notch‚ which serve as reference points. Soft tissue landmarks‚ such as the trachea‚ cricothyroid membrane‚ and carotid pulse‚ are essential for airway management and vascular access. The relationship between fascial planes and compartments is also vital‚ as they house nerves‚ blood vessels‚ and glands. Understanding these landmarks ensures precise dissection‚ minimizing risk to vital structures. They are integral to safe and effective surgical planning and execution in the complex head and neck region.

7.2. Regional Dissection

Regional dissection in the head and neck involves systematic exploration of anatomical structures‚ organized by layers and planes. It begins with the skin and subcutaneous tissue‚ progressing through fascia‚ muscles‚ and neurovascular bundles. Key areas include the neck‚ face‚ and scalp‚ with attention to compartments like the carotid sheath and parapharyngeal space. Understanding the relationships between structures‚ such as the deep cervical fascia and its subdivisions‚ is crucial. Dissection often focuses on exposing vital structures like the carotid artery‚ jugular vein‚ and cervical plexus. This methodical approach aids in identifying pathological conditions and planning surgical interventions‚ ensuring precise and safe procedures in complex anatomy.

Clinical Correlations and Pathology

Understanding head and neck anatomy is crucial for diagnosing conditions like thyroid nodules‚ salivary gland tumors‚ and cervical lymphadenopathy. Anatomical knowledge aids in precise surgical interventions and imaging interpretations‚ ensuring effective treatment of pathologies in this complex region.

8.1. Common Clinical Conditions

The head and neck region is prone to various clinical conditions due to its complex anatomy. Common issues include thyroid nodules‚ which often require biopsy to rule out malignancy‚ and sinusitis‚ involving inflammation of the paranasal sinuses. Tonsillitis and pharyngitis frequently present with sore throat and are often viral or bacterial in origin. Salivary gland disorders‚ such as sialolithiasis‚ can cause pain and swelling. Cervical lymphadenopathy may indicate infection or malignancy‚ necessitating further investigation. Understanding the anatomical relationships helps in diagnosing and managing these conditions effectively‚ ensuring timely and appropriate treatment.

8.2. Case Studies

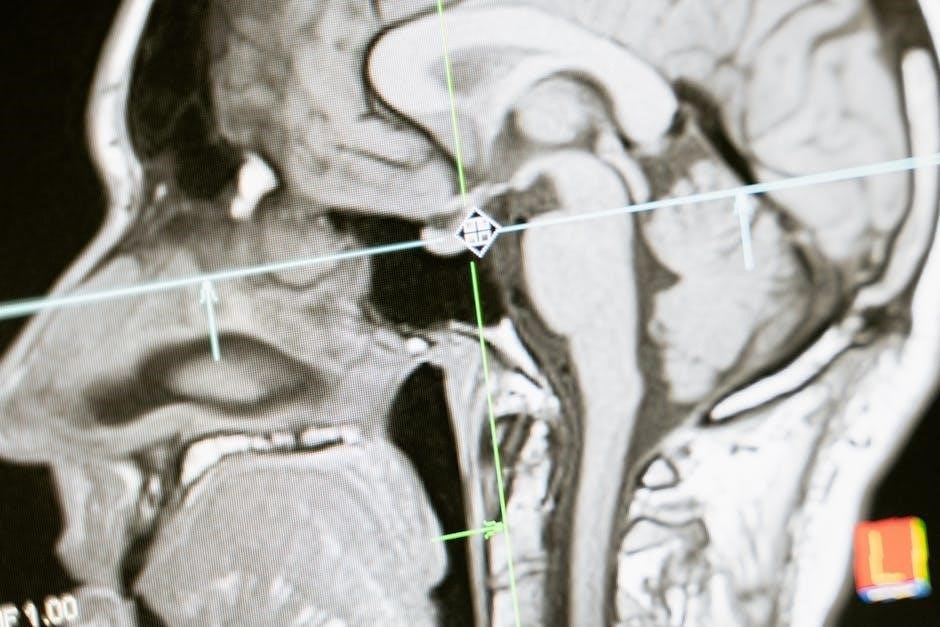

Case studies provide practical insights into the application of head and neck anatomy in clinical scenarios. For instance‚ a patient with a thyroid mass may undergo fine-needle aspiration biopsy‚ guided by anatomical landmarks like the cricoid cartilage. Another case involves a maxillary tumor abutting the orbital floor‚ requiring precise dissection to preserve surrounding structures. A carotid artery aneurysm case highlights the importance of understanding vascular anatomy for successful endovascular intervention. These real-life examples demonstrate how anatomical knowledge aids in diagnosis‚ treatment planning‚ and surgical precision‚ ultimately improving patient outcomes in complex head and neck conditions.

Applied Anatomy and Practical Considerations

Understanding spatial relationships and functional anatomy is crucial for procedures like endoscopic sinus surgery or orthognathic surgery‚ minimizing risks and enhancing surgical precision significantly.

9.1. Anatomical Relationships

The intricate relationships between structures in the head and neck are vital for both function and surgical planning. The skull base serves as a critical junction‚ connecting the brain with facial structures. Major blood vessels‚ such as the carotid artery‚ traverse the neck alongside cervical vertebrae. The airway‚ including the nasopharynx‚ oropharynx‚ and laryngopharynx‚ is centrally located‚ surrounded by muscles and nerves. The thyroid gland is positioned anterior to the trachea‚ while the esophagus runs posteriorly along the cervical spine. Understanding these spatial connections is essential for procedures like tracheostomy or thyroidectomy‚ as they minimize complications and enhance precision in surgical interventions.